Sep 01 2020, by Fleetwood Urban (Marketing)

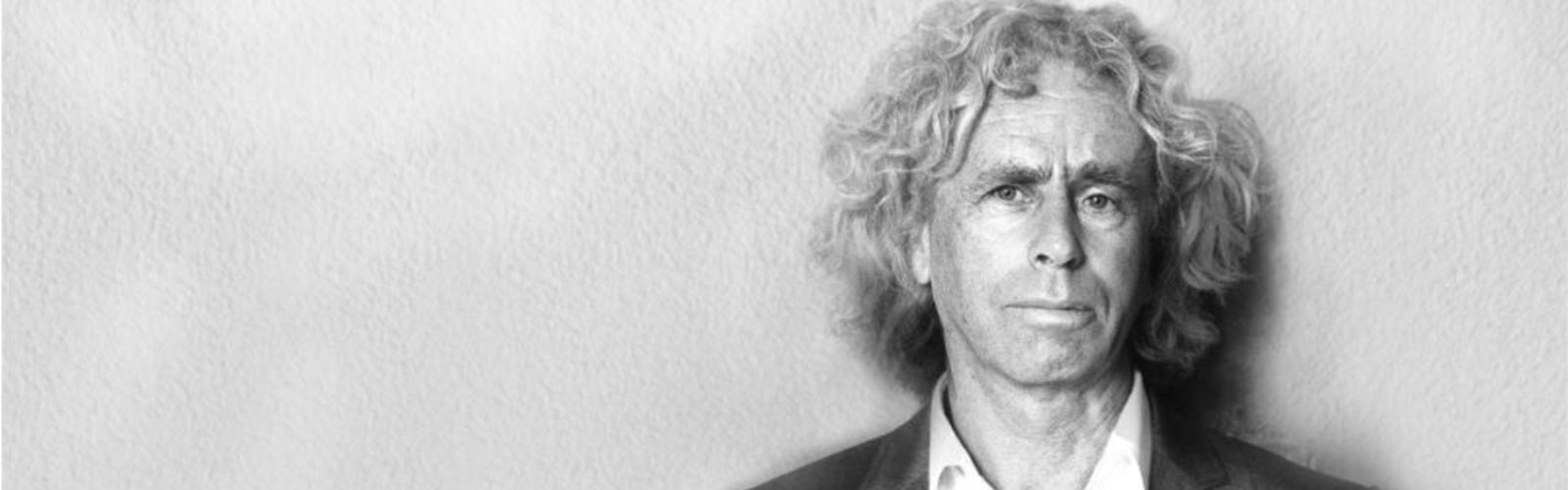

Industry Inspiration: Philip Coxall

Brimming with energy. Overflowing with anecdotes. It’s been well over thirty years since Philip Coxall, now 66, took a giant leap into the unknown to pursue a career in the fledgling profession of landscape architecture. It’s since taken him all over the world, led to a bulging award cabinet and seen him recognised as one of Sydney’s 100 Most Significant People. We were delighted to catch up with Philip recently from his Manly studio, to discuss his career, philosophies and, amongst other things, his love for riding bicycles very long distances.

FWD>THINKING: Philip, was landscape architecture something you always dreamt of doing from a young age?

PHILIP COXALL: (laughs) When I was young there was no such thing as landscape architecture really. Everyone knew about architects, but landscape architecture was still such a young profession. I didn’t even know what it was. In the back of my mind I liked the idea of maybe being an architect, but I was hopeless at maths and hopeless at school in general.

FWD: Hopeless? Or just not that interested?

PC: The system just didn’t fit me, put it that way. There was something about design and invention I was always interested in, but the Uni qualifications (architecture) didn’t interest me. I actually started out doing industrial design as an apprentice in Sydney, that lasted about a year. Then one summer I looked across the street and I saw these guys in shorts and t-shirts, they were building something out of rocks in a garden. I thought ‘wouldn’t it be great to be outdoors in the glorious sunshine?’ I just wanted to be outside doing something interesting.

I went home that night and told my mum ‘I don’t want to do this apprenticeship any more’. I was about 19 at that stage and she mentioned that my sister’s boyfriend’s friend was doing gardening work. I called him up and he said I should study horticulture. I said ‘what’s that?’ He explained it was the study of plants and I thought ‘I‘ve never noticed a tree in my life!’ You have to remember I came from Auburn. There wasn’t a lot of nature around that part of western Sydney, just lots of concrete. Anyway, I called around and managed to get a job at a nursery because part of getting into horticulture back then, you had to be working in the industry.

FWD: Your first tentative step towards the world of landscape architecture?

PC: For a while I just bummed around lifting plants and working at the nursery. It was alright for a young bloke, but I did wonder if there was much of a future in it. Then one day these guys came into the nursery with a truck, they picked up all these rocks and plants and they left. I asked my boss ‘what are they doing?’ He said they were landscapers, and I was like ‘landscapers? That’s what I want to do!’ I had to work in the nursery for another year or so before I managed to get on the truck. Then one day I was working out at Warriewood, digging holes and planting around an old sewage treatment plant. This mate and I were using a post hole digger, it was very heavy, scorching hot, 40 degrees in the sun, burning my arms. We were killing ourselves going up and down on this beast of a thing, and then this youngish guy shows up in a really flashy, sporty Celica. He was wearing these Bermuda shorts and socks, and you could tell the car was air-conditioned, which sure beat what we were doing! He walked over to our boss, pulled out some plans and started pointing all over the place. Then after about 15 minutes he was gone again. I went up to the boss and asked ‘who was that guy?’ and he was pretty dismissive. ‘Oh, he’s the designer’. I was like ‘tell me more!’ I asked my boss what he does. ‘Some thing called landscape architecture’. I locked that away in my brain. Landscape architecture.

After a couple of years on the truck, I left and travelled all around the world. While I was away, I met a German girl but she wasn’t overly impressed with me just being a gardener. Neither was her family, so when things were getting a bit tight about whether they were going to let me marry her or not, I said ‘no, no I’ve got bigger ambitions, I want to be a landscape architect.’ Well, they all raced off to the dictionary to see what that was – and they were impressed, in Germany it seemed to carry quite a bit of kudos. I was pretty much locked into it then!

FWD: So, love forced your hand?

PC: It did. When I came back to Australia, I applied to get into landscape architecture. I applied to all the universities in the first year and didn’t get in. I applied again in the second year and couldn’t get in. But in the third year, luckily for me, there was a terrible drought. A lot of people from the country studied landscape architecture back then, and because of the drought many needed to stay on the family farm. I got a call, two days before the course started from the uni in Canberra saying if I could be there, I could take up a position. It was the best thing that ever happened to me.

I wouldn’t say I excelled from the beginning, but I was very interested and knew I was quite good, I just had so much passion. The other big advantage was I was quite mature by that stage. I started the course when I was 29, I’d travelled, I was married, I knew I really had to make a go of it.

FWD: Let’s fast forward. You’ve been doing this for over three decades now, that’s a long time in any profession. Has it been hard to stay fresh for so long?

PC: The guys I work with still dread the weekends, because I’m always coming in on Mondays full of ideas. I actually had an idea last weekend, it was actually pretty pathetic, but I was just so excited. Here I am at 66 still shaking with excitement about an idea, I feel so lucky that I still get super energised about what I do. I just love design.

FWD: It sounds like your colleagues might describe you as a bit of a mad professor?

PC: Well, I do look a little bit like Albert Einstein! I think they’d definitely say I’m on a slightly twisted end of the human spectrum. But they all respect that energy, it’s a big part of who I am and what I do. I’ll get something in my head, like a design problem to solve, and in my brain it’s like going into a filing system. I start throwing all these ideas around as I begin to put a picture together.

FWD: Has that changed much over the course of your career?

PC: When I first started out, I wanted to be a punk landscape architect. To me, punk was about breaking the system and being disruptive and I thought a lot about how to disrupt with design. I was lucky enough to work in Hong Kong for a while and there were plenty of opportunities to be disruptive there because, to put it mildly, they didn’t really care. I did punk stuff all over the place! But one day, there was an opportunity to design for a client that was far more sophisticated. I went back years later and it was just a magical moment to see it again. It was timeless. It was elegant. I knew that was where I needed to be. At that moment, I realised all the other stuff was just a diversion. I’d found a higher level of quality.

FWD: That’s one of the advantages of having done something for so long, you evolve as a professional and as a person.

PC: What we do is a craft, it’s an art form, and being good at your craft is all about knowing your craft. Take Glenn Murcutt, he’s one of the most beautiful Australian architects. He won the Pritzker award (2002) for architecture which is like the Nobel prize for architecture, he’s the only Australian ever to win it. Glenn’s work is just so elegant. Rather than trying to find ‘different’ every time, he’s a wonderful example that great design is as much about knowing yourself and expressing that time and time again, but better and better and better. It’s like honing a knife. Over time, you’re getting that edge sharper and sharper and, as you do, the steel and the quality is getting better and better. The process of what you produce is just wonderful, always striving for perfection.

FWD: Perfection is the goal, but do you ever get there?

PC: No, but it’s about always wanting to. It’s about what you take out, just as much as what you put in, it’s about trying to find truth in the design and in yourself. As you mature as a person, you learn more and more about your craft, you learn from your mistakes as much as from your successes.

FWD: What advice would you give to a young landscape architect just starting out?

PC: A philosopher once said ‘err and err and err again, but less and less and less’. I really believe that. In the mistakes are your learning, so if I’d say anything don’t be afraid to make mistakes. Go out there and push, because you can lock yourself in later. If you don’t know your parameters and boundaries early on, you’ll never get to know those boundaries.

FWD: You touched on failure before. You’ve won so many awards at McGregor Coxall, but have there been any spectacular failures you’re prepared to share?

PC: It’s such a valuable thing to be vulnerable. One of the most spectacular mistakes we’ve ever made was actually at one of our best-known projects, Ballast Point Park on Sydney Harbour. We designed these amazing wind turbines, but they never worked. They’ve never driven the energy we wanted them to drive because the wind just wasn’t sufficient. We were so in love with the idea of the wind and these turbines that we rushed it. Looking back, we’d probably just turn them into an art piece and leave it at that. In one way I’m proud of that mistake, but I’m also a bit embarrassed.

Just speaking of mistakes, Ballast Point was also the first time we worked with the guys at Fleetwood – and I actually fell in love with them because of a stuff up on that same project! It was a wet day and one of the guys who was delivering the struts for the wind turbines walked all over them and left these dirt stains and mud stains. We’d just had them painted, beautifully done, and I wasn’t happy. ‘Where is that guy?!’ But the guy had already left, so I called up the Fleetwood office, absolutely furious. It was (Fleetwood Director) Ian Joyce on the phone, and he said ‘leave it with me I’ll sort it out’. Well in about an hour Ian was there on the site himself, in his good shoes and pants from the office, with wash cloths and detergent and he hand-cleaned it himself. I was just so impressed. In the old days you’d go and have a very robust conversation and the contractor would probably tell you ‘Get lost mate, it’s only a bit of dirt’. But not Fleetwood. They represent a really humble, caring business – and I always connect with people who care.

FWD: Just one final question Philip. Is it true you once rode 4,000km on a bicycle from France to Gambia in Africa?

PC: Yes, I love challenges and adventure. It’s the most amazing thing to clear the head. I’ve actually done quite a lot of riding in South America and across Europe. In fact, I’m currently looking at taking a sabbatical at the end of next year to ride from Hamburg to Hong Kong across the Silk Road. I remember once I rode across this desert and people said ‘wow, that must’ve been the most boring thing you’ve ever done?’ For me it was the most spiritual thing I’ve ever done. Night would come, the clouds would part and the stars would just drop down like chandeliers that you could almost touch, it was just incredible. It’s the conversations you have too, I remember going on this ride with my son when he was about 17 and he said to me at the end of it ‘I feel like I know you now – and you’re actually not a bad guy!’

FWD: We can only agree with him Philip! Thanks so much for your time.